John Nolan

John Nolan

October 28, 2019

Implementation, maintenance, training, and knowledge products for Information Security Management Systems (ISMS) according to the ISO 27001 standard.

Automate your ISMS implementation and maintenance with the Risk Register, Statement of Applicability, and wizards for all required documents.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an ISMS according to ISO 27001.

Train your key people about ISO 27001 requirements and provide cybersecurity awareness training to all of your employees.

Accredited courses for individuals and security professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 and the ISMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Compliance and training products for critical infrastructure organizations for the European Union’s Network and Information Systems cybersecurity directive.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to comply with the NIS 2 cybersecurity directive.

Company-wide training program for employees and senior management to comply with Article 20 of the NIS 2 cybersecurity directive.

Compliance and training products for financial entities for the European Union’s DORA regulation.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to comply with the DORA regulation.

Company-wide cybersecurity and resilience training program for all employees, to train them and raise awareness about ICT risk management.

Accredited courses for individuals and DORA professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Compliance and training products for personal data protection according to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to comply with the EU GDPR privacy regulation.

Train your key people about GDPR requirements to ensure awareness of data protection principles, privacy rights, and regulatory compliance.

Accredited courses for individuals and privacy professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for Quality Management Systems (QMS) according to the ISO 9001 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement a QMS according to ISO 9001.

Accredited courses for individuals and quality professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 and the QMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for Environmental Management Systems (EMS) according to the ISO 14001 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an EMS according to ISO 14001.

Accredited courses for individuals and environmental professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 14001 and the EMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation and training products for Occupational Health & Safety Management Systems (OHSMS) according to the ISO 45001 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an OHSMS according to ISO 45001.

Accredited courses for individuals and health & safety professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Implementation and training products for medical device Quality Management Systems (QMS) according to the ISO 13485 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement a medical device QMS according to ISO 13485.

Accredited courses for individuals and medical device professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Compliance products for the European Union’s Medical Device Regulation.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to comply with the EU MDR.

Implementation products for Information Technology Service Management Systems (ITSMS) according to the ISO 20000 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an ITSMS according to ISO 20000.

Implementation products for Business Continuity Management Systems (BCMS) according to the ISO 22301 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement a BCMS according to ISO 22301.

Implementation products for testing and calibration laboratories according to the ISO 17025 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement ISO 17025 in a laboratory.

Implementation products for automotive Quality Management Systems (QMS) according to the IATF 16949 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an automotive QMS according to IATF 16949.

Implementation products for aerospace Quality Management Systems (QMS) according to the AS9100 standard.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement an aerospace QMS according to AS9100.

Implementation, maintenance, training, and knowledge products for consultancies.

Handle multiple ISO 27001 projects by automating repetitive tasks during ISMS implementation.

All required policies, procedures, and forms to implement various standards and regulations for your clients.

Grow your business by organizing cybersecurity and compliance training for your clients under your own brand using Advisera’s learning management system platform.

Accredited DORA, ISO 27001, 9001, 14001, 45001, and 13485 courses for professionals who want the highest-quality training and recognized certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 (ISMS), ISO 9001 (QMS), and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Find new clients, potential partners, and collaborators and meet a community of like-minded professionals locally and globally.

Implementation, maintenance, training, and knowledge products for the IT industry.

Automate your ISMS implementation and maintenance with the Risk Register, Statement of Applicability, and wizards for all required documents.

Documentation to comply with ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 22301 (business continuity), ISO 20000 (IT service management), GDPR (privacy), NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity), and DORA (cybersecurity for financial sector).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and security professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 and the ISMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Compliance, training, and knowledge products for essential and important organizations.

Documentation to comply with NIS 2 (cybersecurity), GDPR (privacy), ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), and ISO 22301 (business continuity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and security professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 and the ISMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for manufacturing companies.

Documentation to comply with ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), and ISO 45001 (health & safety), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 (QMS) and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for transportation & distribution companies.

Documentation to comply with ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), and ISO 45001 (health & safety), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 (QMS) and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for schools, universities, and other educational organizations.

Documentation to comply with ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 9001 (quality), and GDPR (privacy).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 (ISMS) and ISO 9001 (QMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, maintenance, training, and knowledge products for telecoms.

Automate your ISMS implementation and maintenance with the Risk Register, Statement of Applicability, and wizards for all required documents.

Documentation to comply with ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 22301 (business continuity), ISO 20000 (IT service management), GDPR (privacy), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and security professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 and the ISMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, maintenance, training, and knowledge products for banks, insurance companies, and other financial organizations.

Automate your ISMS implementation and maintenance with the Risk Register, Statement of Applicability, and wizards for all required documents.

Documentation to comply with DORA (cybersecurity for financial sector), ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 22301 (business continuity), and GDPR (privacy).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and security professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 and the ISMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for local, regional, and national government entities.

Documentation to comply with ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 9001 (quality), GDPR (privacy), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 (ISMS) and ISO 9001 (QMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for hospitals and other health organizations.

Documentation to comply with ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), ISO 45001 (health & safety), NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity) and GDPR (privacy).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 (ISMS), ISO 9001 (QMS), and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for the medical device industry.

Documentation to comply with MDR and ISO 13485 (medical device), ISO 27001 (cybersecurity), ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), ISO 45001 (health & safety), NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity) and GDPR (privacy).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 27001 (ISMS), ISO 9001 (QMS), and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for the aerospace industry.

Documentation to comply with AS9100 (aerospace), ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), and ISO 45001 (health & safety), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 (QMS) and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for the automotive industry.

Documentation to comply with IATF 16949 (automotive), ISO 9001 (quality), ISO 14001 (environmental), and ISO 45001 (health & safety), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 (QMS) and ISO 14001 (EMS) using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

Implementation, training, and knowledge products for laboratories.

Documentation to comply with ISO 17025 (testing and calibration laboratories), ISO 9001 (quality), and NIS 2 (critical infrastructure cybersecurity).

Company-wide cybersecurity awareness program for all employees, to decrease incidents and support a successful cybersecurity program.

Accredited courses for individuals and quality professionals who want the highest-quality training and certification.

Get instant answers to any questions related to ISO 9001 and the QMS using Advisera’s proprietary AI-powered knowledge base.

John Nolan

John Nolan

If your organization has a functional QMS (Quality Management System), whether certified against the ISO 9001:2015 standard or not, you probably have several KPIs (key performance indicators) that help you understand how you are performing with respect to quality. While these may be specific to your organization or the sector you operate in, do your KPIs truly reflect the financial cost to the organization – when poor quality may cost your company money – even beyond the parameters of the KPIs already measured?

The cost of quality can be said to be the definition of time and expenses accrued by an business outside of pre-defined process actions, which need to be undertaken to preserve, improve, or recover the quality of a product or service. The article How to write good quality objectives gave us the opportunity to review quality objectives in more detail. If you consider your own company, many objectives within your QMS will be very easy to define: a manufacturing company might measure “first pass yield” as a critical measure, while a call center might measure response time or customer satisfaction as one of its staple measures. While these may be valid for your business, they also might not tell the whole story.

Product A might fail twice in 100, giving a first pass yield of 98%, and the rework required to the failing part might take 30 seconds to rework and present for retest. Product B might fail once in 100, giving a first pass yield of 99%, but the reprogramming of an onboard component might take six minutes before presenting for retest. Product C might pass manufacturing tests giving a first pass yield of 100%, but field failures and root cause analysis might cost lots of engineering and quality time to fix, and a bill of $10k. According to our staple quality measures, Product B is performing best, product A second best, and Product C worst – but we can see with further investigation that the times and costs we have seen suggest that things might not be so straightforward.

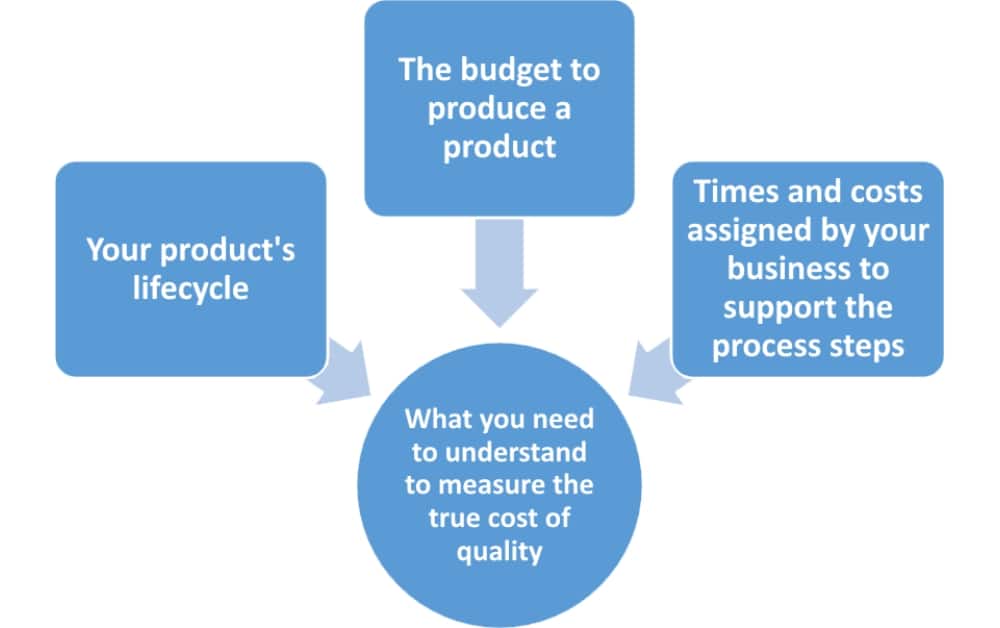

To measure the true cost of quality within your business, you need to truly understand your product’s lifecycle, from design and development to end-of-life disposal. You will then have to take the time to understand what the budget to produce a product is, and what times and costs are assigned by your business to support these process steps.

When you understand this, you can begin to search for the costs associated with your product that are beyond this defined scope. Some examples might be:

Picture two scenarios: a mobile phone with an expected lifecycle of 4 years is found to have an average lifecycle of 3.5 years, meaning an increase in cost to arrange transport back and recycle. Similarly, a television set with an expected lifecycle of 4 years is found, on average, to last 3.7 years. Despite the television performing closer to forecast in terms of lifecycle, the sheer weight of product and cost of recycling would erode the profit on the television product range far more than the telephone. This erosion of profit due to a shorter-than-expected lifecycle can be classified as a true “cost of quality.”

Measuring the “cost of quality” for any business requires some very specific knowledge with respect to the processes, people, and products associated with your business. The ISO 10014 quality management standard can provide guidance here, with respect to both improving quality and controlling associated costs.

Establish “cost of quality” as a measurable KPI, find the root cause, and drive improvement accordingly, and you will be well on your way to establishing a competitive advantage in your sector. This is also directly linked to how your business views and takes action with respect to risk, as we saw in the previous article How to address risks and opportunities in ISO 9001. Lastly, understanding how to use root cause analysis to support corrective action in your QMS can be the method by which you ensure that reoccurrence is prevented in the future.

Finally, measuring the cost of quality can be a very effective way of driving improvement for your business and your customers. Do it effectively and resolve the root causes, and this will surely prove to be a competitive edge for your business.

To implement ISO 9001 easily and efficiently, use our ISO 9001 Premium Documentation Toolkit that provides step-by-step guidance and all documents for full ISO 9001 compliance.

You may unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please see our privacy notice.